Rocks tell a story for contemporary artist

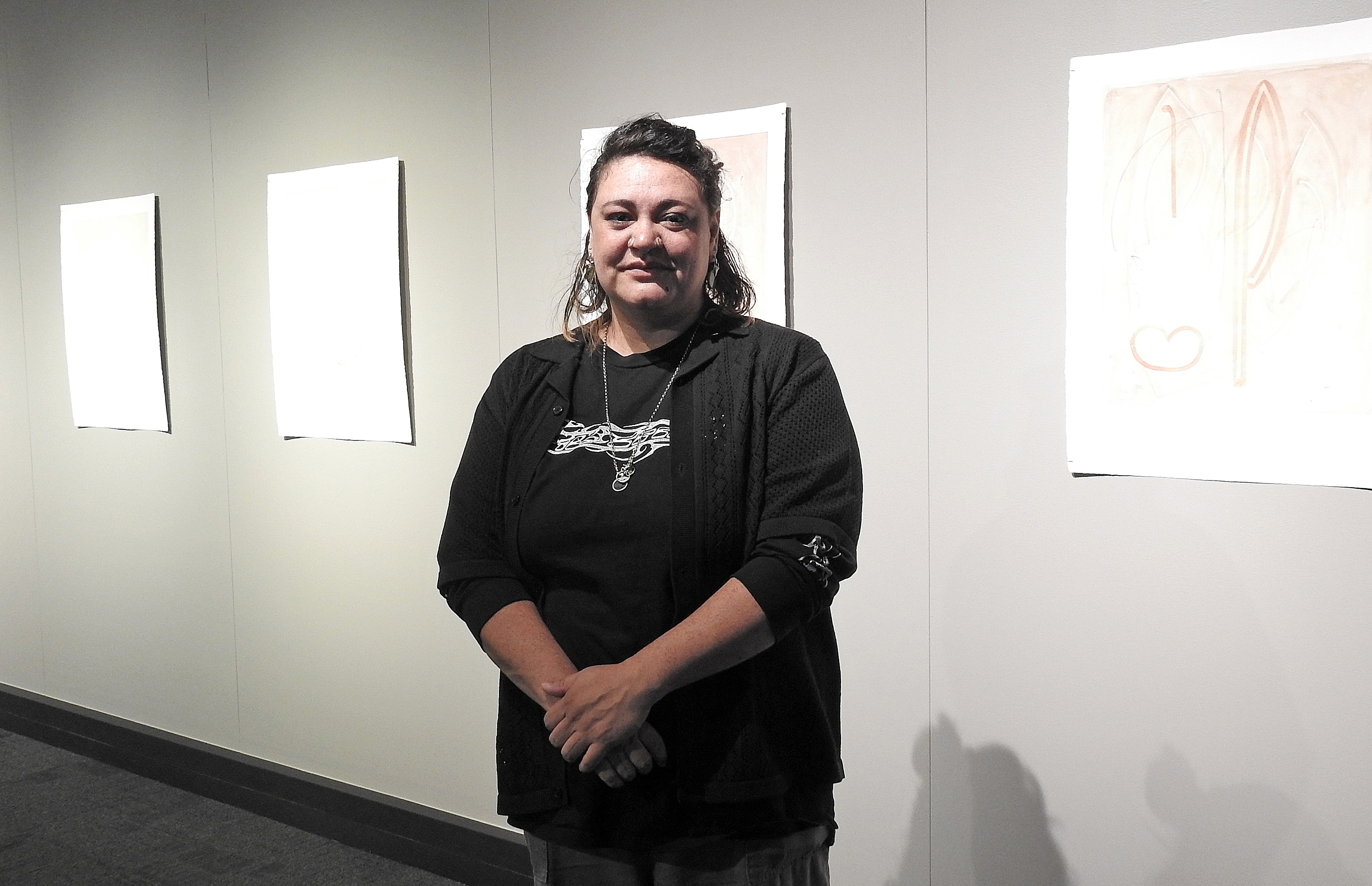

CONNECTIONS: Sarah Hudson has a new exhibition on, The Stones Remember. Photos Kathy Forsyth E5532-04

.

A recent artist residency in Japan has inspired a powerful new body of work by contemporary Māori artist Sarah Hudson (Ngāti Awa, Ngāi Tūhoe, Ngāti Pūkeko), marking her first exhibition in Whakatāne in a decade.

Her solo show, The Stones Remember, opens this Saturday at Te Kōputu a te whanga a Toi – Whakatāne’s public gallery – and will run alongside He Tāwharau Mataatua, a group exhibition, and Rarohenga by Wharerangi Turnbull.

Earlier this year, Hudson completed a month-long residency on Megijima, a small island in Japan’s Seto Inland Sea, through the Naoshima Artist in Residence programme.

The experience became a personal and artistic reflection on place, connection, and memory.

“I was invited to stay on this beautiful small island in Japan, Megijima. It is a similar size to Moutohorā and it is a similar distance to the mainland.”

Home to around 80 mostly elderly residents, Megijima sparked a contemplation in Hudson on the shared dynamics of offshore islands – particularly the contrasts between cultural access and ancestral ties.

“There’s a kind of bittersweet feeling,” she said. “Being welcomed onto someone else’s island, while access to the islands I whakapapa to can be a bit more difficult.

“Both in Japan, and at home, I produced a body of work made up of moving image, earth-pigment watercolours and sculpture.”

The Stones Remember is a multi-media installation that includes moving image and paintings created with earth pigments collected from Moutohorā, made possible through a permit from Ngāti Awa, as well as Japanese indigo, weaving together the landscapes and textures of both islands.

It explores Hudson’s connection to Moutohorā, looking at the space between longing and belonging.

“It has been a year of researching, painting and making, and talking to people about their relationship with the island.”

Drawing on the shared visual language of stone walls on Moutohorā, at Wairaka and Megijima in Japan – rock becomes both boundary and bridge in her work.

Hudson’s residence coincided with the Setouchi Triennale in Japan, where she exhibited.

“This art festival happens every three years to open up these really beautiful places and get the city folk into the rural areas, and they use art as a tourism tool but also create awareness of these places that people are leaving.”

One installation in her show incorporates historical photographs surrounded by rocks.

“The rock wall at Wairaka was made from rocks blasted at Moutohorā and brought here. Some of our ancestral rocks at the river mouth were put into that wall.

“For many of my relations, that wall is the closest connection to Moutohorā – it’s in touching those rocks.”

The project was made possible, she said, thanks to support from the McCahon House Trust together with STILL and the Asia New Zealand Foundation.

Ringatoi and rarohenga explored

The second, group exhibition, He Tāwharau Mātaatua, honours the creative practices of ringatoi who whakapapa to iwi in Mātaatua rohe.

This exhibition pays tribute to the amo from the Ngāti Pūkeko wharenui, Awanuiārangi – now standing at the entrance to the gallery, gifted to Te Kooti at the time of his pardon.

These taonga carry with them the legacy of shelter and protection offered by Mātaatua iwi during times of immense political and cultural tension.

Wharerangi Turnbull invites viewers into a glimpse of Rarohenga – the realm and origin of tā moko – through Mataora and Niwareka.

This becomes a space of learning, reflection, and reconnection, where tā moko is honoured as a transformative and healing practice grounded in pūrākau.

Wharerangi works alongside Te Wehi Preston and the kaupapa-led Moko Ora collective, dedicated to strengthening the cultural foundations of tā moko and the sharing of mātauranga.

Take a look around

Sarah Hudson also has an installation in the Trust Horizon Light Up Festival, titled He Tohu.

“I have used a VMS, a traffic messaging board, which draws attention to the natural world, rather than our busy day-to-day world.

He Tohu means “a sign”.

“Once upon a time, and still now, tohunga would get signs from nature, rather than on their phones or digitally, so it sends a message for people to go for a walk outside and have a look around.”