Opinion: What are rare earth minerals and why should anyone care?

.

Anyone reading our national newspapers or listening to TV shows like Q+A, and especially the July 7 episode in 2024 , will have heard Minister Shane Jones wax lyrical about critical minerals and mining, writes Victor Luca.

He has used the expression “dig baby dig”, which is a variant of the “drill baby drill” expression much used by US President Donald Trump.

Mr Jones is our Minister for Regional Development, Resources, Oceans and Fisheries and Associate Minister of Finance.

The recording of his Q+A contribution had been viewed more than 53,000 times shortly after it aired.

Mr Jones follows a chorus of experts and commentators the world over talking about critical minerals (or materials) including Trump.

It would seem that neither Mr Trump nor Mr Jones have much of an idea about these minerals despite having talked about them so much lately.

Critical minerals are a group of minerals essential for modern technologies and industries, such as those used in clean energy, electronics, and defense applications.

Many countries compiled critical materials/minerals lists long ago and we have now followed suit.

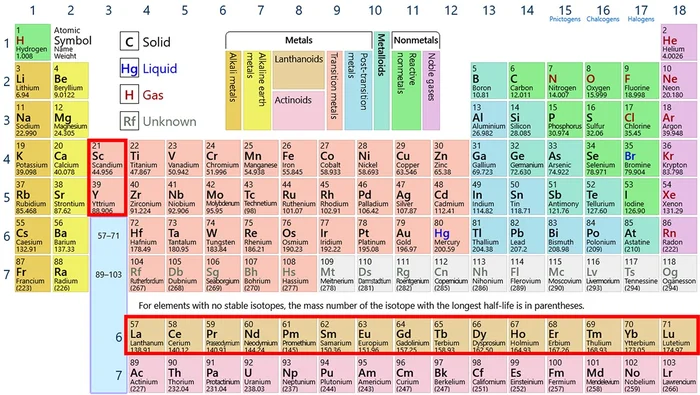

Our variant of a critical minerals list comprises 37 of the 118 elements in the periodic table of elements which we learned about in secondary school.

Of the 37 minerals in our list, we have 26 in common with the Australian list.

Included on our list are exotic-sounding elements such as tungsten, antimony, gallium, germanium and indium. Among the most talked about are the so-called Rare Earth (RE) elements that are essential in many modern technologies.

The term Rare Earth was first suggested by Johann Gadolin in 1794.

The minerals were considered “rare” when the first of the RE elements were discovered as they were thought to be present in the Earth’s crust only in small amounts. The “earth” part is because, as oxides, they have an earthy appearance.

Mr Trump has referred to RE minerals by the misnomer of “Raw Earths”, showing he has no idea what he’s talking about and was either reading speech notes or was parroting something that a little birdie whispered in his ear but didn’t stick.

On the Q+A episode, Mr Jones referred to antimony as a RE mineral, which it is not.

So, clearly he didn’t do chemistry at St Stephen’s School or hasn’t looked at a periodic table lately.

The RE elements are a group of 17 elements including the 15 elements on the sixth row of the periodic table or (elements 57 through to 71) plus scandium and yttrium. Antimony on the fourth row is element 51 and is definitely not a RE element.

The RE elements often occur together in the minerals found in rocks (eg, phosphates, fluorocarbonates and clay minerals) because they have similar chemistry.

For this reason they also tend to be difficult to separate one from another.

The chemical processes required for the separation of individual REs are complex, messy and very environmentally unfriendly as well as energy and water intensive.

Because of this, and because it couldn’t compete with Chinese production, the United States’ only RE miner went bankrupt and shut down their Mountain Pass mine in California in 2015. The mine has recently been resuscitated by MP Materials Corporation.

I spent a couple of decades trying to develop novel clean methods for separating one RE element from another. Although RE elements were once considered rare, they are anything but. Those that are used the most are as common as copper or lead.

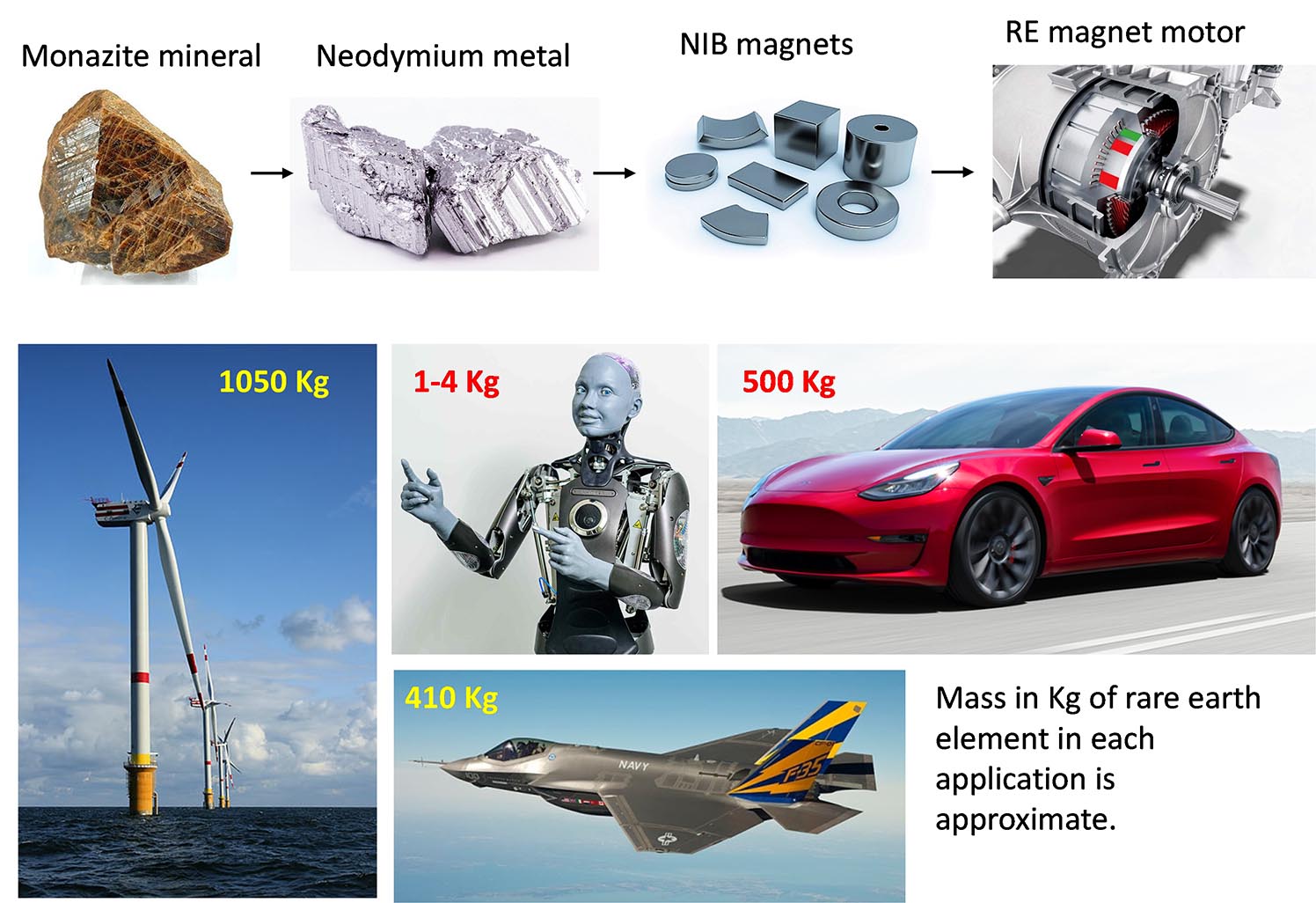

RE elements like neodymium are critical elements in very strong permanent magnets required to make powerful electric motors such as those used in electric vehicles.

These magnets are also essential in wind mills, battery powered hand tools, industrial and humanoid robots and so on. They are usually made of an alloy of the RE element neodymium combined with iron and boron (NIB).

Other RE elements like dysprosium and terbium can also be used to make magnets for certain types of motors. RE elements are also used in a wide range of electronics and in automotive catalytic converters.

The RE elements can also become radioactive when they are exposed to neutrons and so they are also relevant to the nuclear industry. Hence my initial interest.

Because of the relationship to my work, in about 2010 I decided to invest a few bucks in the RE mining sector.

At the time China dominated RE mining, processing and refining and it still does; more than 60 percent of mining and 85 percent of refining. In 1992 Deng Xiaoping made the statement, “The Middle East has its oil, China has rare earths”.

In 2010, China applied restrictions of RE supply to Japan as a result of a spat over fishing trawlers.

This got everyone very worried about the control that China could play over the RE supply chain and the prices of the RE mineral prices shot up dramatically.

Aside from RE elements, there are many other critical elements.

For instance, tungsten is one critical element that is required to produce almost any machine tool. Without machine tools we couldn’t make much out of metal.

The metal rhenium (Re) plays a critical role in modern jet turbine engines, particularly in superalloys used for high-temperature components.

Without rhenium, modern air travel would be impossible. The tactile displays in mobile phones require indium.

Although most people will not have heard of many of the elements I have mentioned, our modern-day lifestyle would be impossible without them. A transition to clean renewable energy would be impossible.

Mining is a tough, complex and highly competitive business and although I started making very modest investments in Australian RE mining companies for over a decade, it has certainly not made me rich. I guess I can only hope.

Folk like Mr Jones don’t seem to realise that it can take many years to get a mine into production, and that is after the discovery of the ore body.

Development of a mine and a process for mineral extraction often takes huge sums of money and time and is not for the faint hearted.

Yet, our minister makes it all sound easy. While important, consenting is but one step. Even if consenting can be fast-tracked there are many other steps to follow. Consenting is not necessarily the rate-limiting step in developing a mine and processing facility.

The multi-mineral Toongi deposit, near Dubbo in New South Wales, contains Zr, Nb and REs and was first identified in the late 1980s and has an estimated mine life of 40 years.

While lots of hydrometallurgical process development and engineering design work has been undertaken and all the permitting is in place, there is no working mine yet.

Once an ore body has been completely defined in three dimensions using all sorts of geophysical techniques and lots and lots of drilling and chemical analysis, only then can a Bankable Feasibility Study (BFS) be produced.

A BFS is a comprehensive and detailed technical and financial assessment of a mining project that determines whether it is economically viable, technically sound, and suitable for securing financing from banks or investors.

Once a BFS has been developed and risks understood, the raising of capital remains as a huge mountain to climb. The RE mining company I have been talking about requires upwards of billion dollars to develop the mine and more for the downstream processing.

Australia is a mining friendly jurisdiction and Australians have a long tradition in mining. There are over 7000 active mining companies in Australia, about 730 of which are listed on the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX).

Australia is 29 times the size of New Zealand and much of the land is not exactly highly productive, at least in an agricultural sense. Australia possesses the technology and considerable know-how in most aspects of mine production and some capability in downstream processing.

When it comes to mining, it is very much about ore grade, depth, ease of extraction and processing, energy consumption and location of the mine site to major infrastructure.

Whatever we do in the mining space in New Zealand would pale in comparison with Australia.

It would be difficult to imagine how we could compete for scale, and cost of production, unless we have some specific advantages.

While there could be some low-hanging fruit, one would need to be very clear about one’s competitive edge. And the competition is not just coming from Australia.

Finally, one should forget the role that supply-demand dynamics can play.

Although there is no harm in aspiring to make the grade, we would do well to temper our expectations. Mining is bloody hard yakka.

Although it is easy for politicians to mouth off, I have waited for 15 years for my very modest RE mining investments to pay off.

And, I aint no millionaire yet.