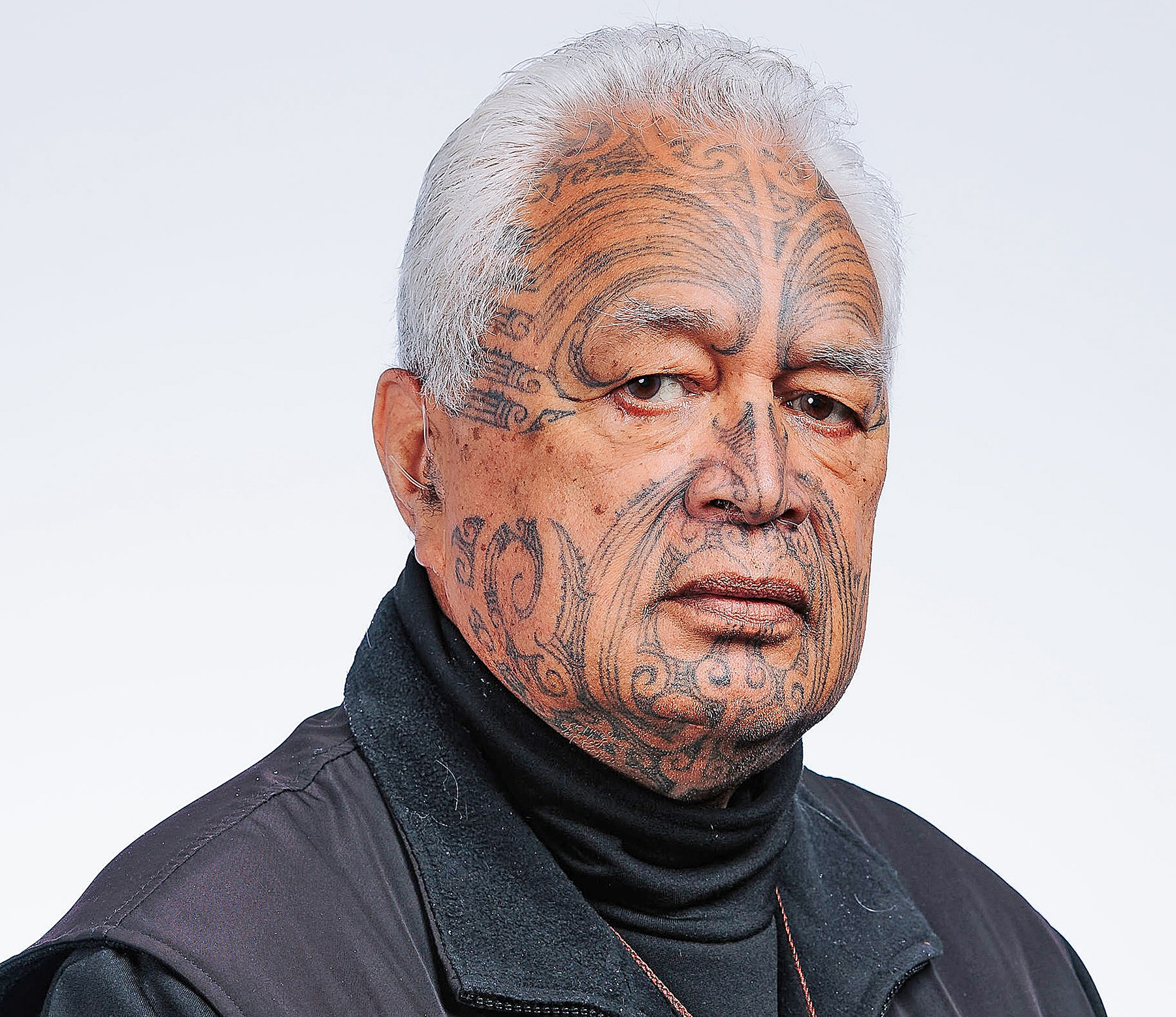

New Year's honour for Joe Harawira

News Editor

Joe Harawira has seen hundreds of people receive royal honours and, after a lifetime of service to Māori education, arts and conservation, it’s his turn.

Mr Harawira (Ngāti Awa, Ngai Te Rangi, Ngāti Maniapoto, Tūhourangi) was named a Companion of the King’s Service Order in the New Year Honours List 2026.

The honour is recognition of more than 45 years of dedication by Mr Harawira across a range of sectors.

These days, Mr Harawira splits his time between being kaumātua to the Governor General, pouwhakahaere with the Department of Conservation, responsibilities within Ngāti Awa and a continued commitment to oral storytelling.

Mr Harawira was born and raised in Whakatāne, then did most of his high school education at Auckland Māori boys’ boarding school St Stephen’s.

He went straight to Hamilton Teachers’ College, graduated in 1977, and spent 14 years as a Form 2 (Year 8) classroom teacher and deputy principal of a total immersion school in Huntly.

A decade as an advisor in Māori education at Hamilton Teachers’ College followed.

At the turn of the millennium, Mr Harawira took a job with the Department of Conservation as a kaupapa atawhai manager that had been recommended to him.

The role required him to liaise between government departments, iwi and hapu, and all conservation managers.

The application form sat on his desk for two weeks while Mr Harawira was busy doing other things.

When he did eventually look at it, he decided it looked like a bit of him.

“I didn’t know anything about conservation – well, I didn’t think I did – but I went and applied.”

As a former teacher, he immediately advocated for DoC to incorporate education into its strategy, because he recognised that connecting children to the heartbeat of the land and getting them to know the natural world was important to effect change.

“It took me 13 years to get a strategy in the Department of Conservation.”

The job has remained consistent in the past quarter century in the realm of Treaty negotiations, iwi engagement and professional development.

Mr Harawira’s interests have always laid in the performing arts.

The roots of that interest formed at the Whakatāne Māori Youth Club where his mother was the kaitataki (tutor). At about six or seven years old, Mr Harawira would tag along to the practices.

He would go on to be involved in kapa haka throughout his schooling, becoming the leader of the St Stephen’s School group in his final year, 1974.

That continued into tertiary study, where Mr Harawira became the leader of the kapa haka of Te Whare Wānanga o Waikato. It’s a role he held for 32 years.

Mr Harawira became involved in judging regional competitions during that time.

In 2007, Mr Harawira took a step back from his group and ended up in the radio booth of national Māori performing arts festival Te Matatini, translating every performance into English in real time for 30,000 people in the audience.

Mr Harawira was asked to judge the competition in 2009, having by then officially retired from performing. He continued to do so annually, several times as head judge, until the 2025 competition in Taranaki.

He was made a life member of Te Matatini and Tainui Waka Cultural Trust in 2018, and he’s looking forward to attending next year’s event just to watch, though he expects it will be difficult to completely remove the judging lens.

Mr Harawira is a renowned oral storyteller, which he credits to the wealth of drama and theatre education at St Stephen’s School.

He would attend international storytelling festivals, often one of only a few oral storytellers in a sea of written-word authors.

“That journey was a great journey. I’ve travelled the world for 36 years as a storyteller, been to just about every country in the world telling stories – our Māori stories.”

Mr Harawira said he quickly learned that international audiences loved the Māori language. Whether he was in France, Russia or Germany, he was encouraged to tell his story first in te reo Māori.

He would then tell the exact same story in English, which was translated by an interpreter into the audience’s native language.

As the opportunities arose, Mr Harawira would travel to speak with groups outside of the festivals.

He was in Germany for the 2012 Frankfurt Book Fair – New Zealand was the guest of honour, taking a large contingent of Kiwi authors to the event – when he nipped off to tell stories at a local school for children with behavioural issues.

Mr Harawira said he was warned the classroom of eight-, nine- and 10-year-olds would likely be climbing the walls within five minutes of him starting, but he was unperturbed.

A few minutes into his korero, Mr Harawira noticed a little boy in the corner talking over him. He was translating Mr Harawira’s English words into German.

So, Mr Harawira invited him to the front of the class.

“I told the story in te reo Māori first. It was about 15 minutes, very expressive actions, voices. The actions portrayed the story, even though they didn’t understand it.

“Then I translated exactly the same story into English with the same voices and actions.

“And this young boy, he was right there with me; the voices, the actions, the expressions.”

About six weeks later, Mr Harawira received an email to say the boy had been moved to a mainstream school.

“I say to teachers, your role is to ignite the potential in a child. Every single child in that room has potential. It just takes someone to ignite it.”

Mr Harawira believes in the power of storytelling and though he has not travelled overseas for it since Covid, he continues his mahi in New Zealand.

He tells stories at the series of one-week, total immersion, cultural safety wananga DoC holds for its staff throughout the year.

“We take them through Māori beliefs and values, the Treaty of Waitangi, how to engage with people.

“We tell them, the reason we take you through this is because you are making decisions for me about conservation lands. And we want you to make good

decisions, based on the right understanding of how we practise kaitiakitanga.”

Mr Harawira was instrumental in the reopening of St Stephen’s School, he appeared in Air New Zealand’s ‘Tiaki and the Guardians’ safety video, he is the Kāhui Māori pou tikanga for Sustainable Seas and is on the board for Save the Kiwi.

Although he turns 70 next year, retirement is not something Mr Harawira thinks about, and he believes the variety of his work keeps him young.

“I don’t think Māori ever retire. People like me who wear so many hats, you can retire from the public service, but you can never retire from your iwi and your hapu.

“They’re always there and they’ll always pull you in.”

Mr Harawira does not seek recognition, but he acknowledges that his King’s Service Order honour represents a lifetime of consistency in education, conservation, culture and arts.